Professor Asrat Woldeye’s Brief History

Professor Asrat Woldeye’s Brief history

Professor Asrat Woldeyes was born in Adddis Abeba, on June 20, 1928. When he was barely three years old, his family moved to the south eastern Ethiopian town of Dire Dawa. He was an eight year old boy when Italian Fascist occupation forces of Mussoloni invaded Ethiopia. Following the attempt on the life of the Italian fascist general Grazianni in Addis Abeba on that fateful day of 19 February 1937, his father, Ato Weldeyes Altaye, was captured and brutally murdered along with thousands of other civilians and patriotic Ethiopians by the invading Italian fascist forces. His grandfather, Kegnazmatch Tsige Werede Werk, was one of the Ethiopian patriots who was deported to Italy and stayed there for three and half years along many other Ethiopian resistance fighters.

As if the unfortunate death of his father was not enough, the future surgeon was struck by bouts of another misfortune i.e the loss of his mother W/o Beself Yewalu Tsige, who died of bereavement caused by the untimely and brutal death of her husband. In spite of having been struck by a paroxysm of traumatic events at such prime age, the future surgeon diligently struggled on to find his bearing and maintain his gait through the tumult and insecurity created by the sudden loss of his beloved parents at such youthful age when he needed their emotional support and parental guidance. Following the defeat of the Italian fascist occupation forces in 1941, the future surgeon came to Addis Abeba to pursue his education.

In 1942 he joined the then prestigious Tafari Mekonnen School. He was an outstanding student and in 1943 he was rewarded a camera for having been the best student of the school in that academic year. From Teferi Mekonen school, he was sent to Egypt to pursue his education at Victoria college. Subsequently he was sent to UK where he joined the Medical Faculty of Edinburgh University and studied medicine. He was the 42nd student from among the Ethiopian students that were sent abroad in the post-liberation period. Untempted or untitillated by the glitter and glamour of western life, he immediately returned to his native country upon completion of his medical studies in 1956. After having served his country as a general practitioner for 5 years in the former Prince Tsehai hospital of Addis Abeba, he returned to Edinburgh (Scotland) where he specialized in surgery.

He was the first Ethiopian surgeon in the post-1941 period.

Professor Asrat is the founding member of the Ethiopian Medical Association (EMA), Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Scotland (FRCS Edinburgh) and FRCS (England), member of the British Medical Association (BMA), the East African Surgical Association (EASA) and International College of Surgeons (USA). Since his return to his beloved country Ethiopia, Professor Asrat Woldeyes has given extraordinary medical service to his country both as a practicing physician and professor of surgery at the Addis Abeba University Medical Faculty in the establishment of which he played an important role. The medical school, in which he subsequently served as dean and professor of surgery, came into existence in 1965 as part of the Haile Selassie I university (as it was then called). II – The Disruption of Educational Development in the 1936-1941 Period – A Negative Legacy of Fascist Italy’s Occupation of Ethiopia. Fascist Italy’s occupation of Ethiopia deprived the country a generation of fledgling modern intellectuals. The few hundred Ethiopian intellectuals the country produced prior to 1935 were the primary targets of Italian fascist occupation forces and were accordingly hunted down and physically decimated for fear that they would serve as potential leaders of the resistance movement against Italy.

When the Italians left Ethiopia after 5 years of unsuccessful occupation, there was no trace of an Ethiopian intellectual elite to man or run the modern administrative machinery and shoulder the responsibility of reconstructing the war-ravaged country.

Ethiopia had to wait 12 years after liberation before the first graduated nurses appeared on the scene and wait another 14 years (after liberation) before the first Ethiopian medical doctor (professor Asrat Woldeyes) has to appear on the scene. He was one of the first educated Ethiopians to appear on the scene in a country where the manpower vaccum created due to the unfortunate, if outrageous, extermination of Ethiopia’s few intellectuals by Italian fascists and their 100,000 strong bandas (as these soldiers of fortune are called by Ethiopian patriots) or askaris between 1936-1941 meant that Ethiopia has to start ex nihilo trying to produce anew its educated elite. It also meant a painful, if intolerable, dependence on expatriates during the two decades following the liberation of Ethiopia. Expatriates had to devise plans and set up priorities for Ethiopia about which they knew or cared to know little. This surrender of decision making process to expatriates has had many untoward or negative effects on a developing nation’s life like that of Ethiopia. It was these foreign experts, a good number of whom had no concern for the interest of Ethiopia, that decided what was good or bad for Ethiopia. More often than not, it was the views of these “omniscient” expatriate experts which had an overriding role or sway in shaping the national developmental policies and setting priorities of Ethiopia. Perhaphs nowhere was the ill-advised policies of these “omnisicient” international experts and advisers so evident as in the area of Ethiopia’s public health problems. These experts advised Emperor Haile Sellase’s government on the non advisability and impracticality of establishing a medical school in Ethiopia. Of course any sane person can understand the implications of such advice. It implies not being able to produce nationals locally who can best solve their country’s problem head-on. It implies a humiliating and continued dependance on expatriate medical doctors who could not even directly communicate with the Ethiopian people they are meant to serve due to the language and cultural barrier such an encounter would entail. In a field like medicine, the medical professional’s knowledge and mastery of the language, culture and social background of his/her would-be patient remains to be an important asset in understanding, diagnosing and treating this patient.

The few Ethiopian professionals like professor Asrat had to fight hard to overcome these obstacles that were being put on their way by foreign expatriates who tried to block or delay the establishment of a medical school in Ethiopia. Service as a Medical Practioner and Professor of Surgery Professor Asrat vigorously struggled along with his few Ethiopian colleagues to create the first medical school in the country. This medical school came into being in 1965. And since its opening, the school of medicine has produced hundreds of medical graduates.

Thanks to the effort of medical professionals like professor Asrat and his colleagues such as professors Ededmariam Tsega, Paulos Quana’a, Nebiyat Teferi, Demisse Habte, etc the school of medicine has begun to locally train various medical specialists in such fields as Surgery, Internal medicine, Gynecology and Obsteterics, Opthalmology and Pediatrics. This is an achievement we owe primarily to people like Professor Asrat and his few colleagues who have dedicated their time to create such fine national institutions that can serve the needs of their population.

It is all the more surprising, though, that such national figure of extraordinary caliber has to be dismissed from the University along with 41 other senior lecturers and professors because of his political opinion. In present-day Ethiopia, where might becomes right; omnipotent ex-rebel leaders and misfits of society can become “omniscient academics” that can evaluate, dismiss and lay off at will independent-minded and “incorrigible” intellectuals.

The present anti-intellectual campaign of the EPRDF government parallels that of fascist Italian period in its methods, in its anti-Ethiopian goals. In its drive and cruelty, EPRDF’s current action surpasses the anti-intellectual campaign of the Chinese Cultural Revolution of Mao Tse Tung and Cambodia’s Pol Pot in that the latter two were motivated by communist ideological infatuation (directed against Chinese and Cambodian intellectuals irrespective of their ethnic origin) while EPRDF’s anti-intellectual campaign is motivated by an ethnic hatred directed against non-Tigrean Ethiopian intellectuals.

Until his outrageous dismissal from the Addis Abeba University medical school and teaching hospital in March 1993, Professor Asrat had served his country for 38 solid years. The Dergue Period (1974-1991) In the hey days of ideological infatuation, many issues of national concern had to be decided by ideologically motivated cadres that had hardly any grasp of practical issues. Ethiopia became a country where the decision-making process came to be dictated by the all pervasive ideology in wide currency then i.e socialism. Ideology assumed supremacy over professional competence and merit. This pervasive ideological supremacy over professional commitment was also to encroach upon the health sector. Ideologically-motivated, inept cadres who were for the most part people that knew little about the country’s health problems tried to revise and rewrite the medical school curriculum and define priorities regarding Ethiopia’s health manpower training. Few summoned up their courage to challenge the diktat of these ideologists. True to character, it was individuals like Professor Asrat who had the courage to challenge such sweeping and ill-advised revisions at a time when such opposition amounted to an act of defiance against socialism and the revolution – two sacred concepts in the Ethiopia of the mid and late 1970s.

Since Ethiopian national interest was at stake, Professor Asrat never yielded to the blackmails nor the diktat of these cadres who tried to dictate terms regarding the medical curriculum or health manpower training issue in Ethiopia. Speaking on this important issue of health manpower training in Ethiopia when he addressed the eleventh Annual National Conference of the Ethiopian Medical Association (EMA) in 1975, Professor Asrat had the following to say :

“It is, however, unfortunate that this important theme (the issue of health man-power training and medical curriculum of Ethiopia) has dwindled to an adulteration as it is being used by some self-styled intellectuals, to cover their own failures in life and promote their selfish motive and cover up their defects. In appearing to be saviors of the common man, they (these cadres) tell them he only needs more medical health workers that are trained in a short period. Such a concept is not knew and this was what the colonial powers in Africa did and preached. In the French colonies, the African could only go as high as the level of “medecine Africaine” or Assistant d’etranger (African Doctor or the Foreigner’s assistant). Such cadres of workers were to function as paramedicals to help and assist the well trained European master who forever occupied the position of the unattainable. The very people who preach such doctrines for their countrymen, have no hesitation of employing doctors irrespective of their competence, as long as they come from other countries”.

Such principled stand on issues of national interest has earned Professor Asrat and his few colleagues the then popular label “die-hard, conservative, bourgeoisie reactionary intellectual, etc”. This was an insult courageous people like him had to bear or stomach because of their professional defiance against an inept regime and system that tried to impose its own diktat on the medical profession and system. Few Ethiopian professionals have shown such professional defiance which, in those terrible days, amounted to risking one’s career, and above all, one’s life at a time when ideologists and cadres dictated terms and opposition to their diktat amounted to national treason. Contrary to the allegations of the groups that are currently in power, professor Asrat was not a yes-man that appeased and is willing to appease those in power – past or present. He has always been a man who spoke out his mind regardless of the consequences which such “defiant” behaviour would entail. If readers need more proof about professor Asrat’s determination to defend the truth without any regard for its consequences, here is one more example of his confrontation with the Dergue regarding the circumstances around the death of the late emperor Haile Selassie. Here is what professor John H. Spencer wrote in testimony about the courage of professor Asrat in his monumental book entitled “Ethiopia At Bay : A Personal Account of Haile Selassie’s Years”. Spencer wrote :

“The Dergue announced that Haile Selassie had been found dead in bed and that it had immediately summoned the former emperor’s physician Dr. Asrat Woldeyes. With considerable courage, the doctor publicly denied any such summons. He had been at home all day and no such call had ever reached him”.

In 1980, at the height of the war in the north, professor Asrat was sent to the northern town of Mistswa. Here he had to treat war causalities that fell on both sides of the warring factions. For the Tigrean elites who are currently in power in Eritrea and Ethiopia, professor Asrat’s service in Mistswa was an act of cooperation with the defunct former military regime. As such following EPRDF’s assumption of power in Ethiopia, professor Asrat was subjected to an intense campaign of character assassination by EPRDF controlled newspapers and magazines like Efoyta, Maleda, Abiyotawi Democracy, Addis Zemen, the Ethiopian Herald, etc. Answering to these outrageous charges in 1993, Professor Asrat stated that :

“According to medical ethics and the oath any medical doctor swears, it is the duty of every medical doctor to treat all those who present themselves with medical problems. In this sense, in my capacity as a medical doctor, I have treated the late Emperor Haile Selassie and the family of Mengistu Haile Mariam in the yester-years. At the same time, through out my life, I have been treating many poor Ethiopians who could not afford to pay anything for their medical care. And I am still doing that and it is my duty to treat all those poor who helplessly lie on the streets and come to seek my professional help. I am duty bound to treat any one that comes to my attention to the best of my ability and expertise. If it is their wish I am also prepared to treat members of the present ruling groups (EPRDF/TPLF) when and if they need my help since it is my professional duty to treat and help them (irrespective of their political views, etc) should they need my help”. – Altruisitc Service and Medical Ethics (1956-1993)

In spite of his extensive surgical skills and knowledge, professor Asrat has never been tempted to use his skill and knowledge to enrich himself or neast his feather. He was not one of those medical doctors who set up private clinics to line up their pockets. Had that been the case, today he could have been one of the few Ethiopian millionaires par excellence and his place would not have been in the verminated prison cells of Kershele at such an advanced age. But he is not a man that runs after money or self aggrandizement. He is a very God-fearing and ethical surgeon who leads a very inconspicuous, simple and humble life. It was these altruistic qualities and his life-time professional service and commitment to the Ethiopian people that earned him a glorious name worthy of respect and panegeryisim among the people of Ethiopia of all ethnic and religious groups who have come from all corners of Ethiopia to seek his professional help. This simplicity endeared him to all his colleagues and his patients.

…………………………………….

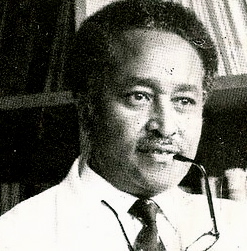

Prof/Dr. Asrat Woldeyes

As political prisoner, party leader and eminent surgeon, he fought for the unity of Ethiopia.

Brian Barder

Tuesday May 25, 1999

Professor Asrat Woldeyes, who has died aged 70, was successively Ethiopia’s most distinguished surgeon, physician and university dean, most controversial political party leader and best known political prisoner. He was also Haile Selassie’s personal physician until his mysterious death in 1975 (in 1996 he was brought from prison to testify that the emperor had not died of natural causes).

Professor Asrat, who was the first Ethiopian to qualify as a surgeon in the west, after medical studies at Edinburgh University, devoted most of his working life to surgery at the two main hospitals in Addis Adaba, and to the deanship of medicine at the university. He could have practised in incomparably better conditions in the west – and for greater rewards – but he preferred to serve his people.

During the dark years of the military communist regime of President Mengistu Haile-Mariam (1974-1991), Asrat continued his medical and university practices. During the 1984-86 famine, his surgical skill saved the life of the Guardian correspondent, Jonathan Steele, who described the event in an eloquent article in the Guardian Weekend magazine last November.

Following the Eritrean-Tigrayan overthrow of Mengistu in 1991 and the independence of Eritrea, the Tigrayan-dominated government increasingly purged members of the Amhara ascendancy, which had dominated the Haile Selassie and Mengistu regimes. Asrat was among 21 Amhara professors dismissed from the university in 1993. In that year he became founder-chairman of the All Amhara People’s Organisation (AAPO), dedicated to bringing back the unity of Ethiopia prior to Eritrean independence and the protection of Amhara interests under the ethnically-based constitution of president (now prime minister) Meles Zenawi.

Although AAPO remained nominally legal, its relations with the Meles government deteriorated and in June 1994 Asrat was arrested. He was imprisoned for two years on charges of planning violence against the state, although Amnesty International and other independent observers pronounced the evidence against him dubious and unsafe, and Asrat was on record as condemning violence for political ends. Further convictions followed, each on similarly unsatisfactory evidence, extending his sentence to five years. In 1996 he faced a new trial, repeatedly adjourned and never completed, clearly signalling the government’s intention to keep him in prison beyond the expiry of his existing sentences.

By now in his late 60s, and with a heart by-pass, Asrat was incarcerated in a communal cell but forbidden to communicate with his fellow prisoners – a refined form of solitary confinement. His health deteriorated and in January 1998 he was transferred, under armed guard, to his old hospital, Tikur Anbessa (Black Lion). By November he was in intensive care. Medical details were kept secret, but news of his heart condition, the onset of diabetes, high blood pressure, deteriorating eyesight and a suspected blood clot on the brain caused growing anxiety. His government-appointed doctors reportedly said that to survive, Asrat needed treatment not available in Ethiopia.

On (western) Christmas Day, 1998, the government finally yielded to international appeals for him to be allowed to go abroad for treatment. Asrat was flown to London and then to Houston, Texas. He appeared to recover, but suffered relapses and died at the hospital of the University of Pennsylvania after less than five months of freedom.

Asrat was a man of great dignity and courtesy, stubborn to the point of cussedness, arguably politically naive. Throughout his five years’ harsh imprisonment, Amnesty International, with other humanitarian organisations and numerous individuals, including now elderly Scottish doctors, campaigned for his release. Until very late, however, western governments, whose intervention might have carried weight with the Meles government, refused to go beyond occasional expressions of concern, apparently fearing to irritate a regime which, despite obvious shortcomings, was pro-western and a vast improvement on its predecessor.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion, though, that if those governments had worked harder and earlier, they might have averted the premature death of the most distinguished, and one of the most courageous, Ethiopians of our time.

• Asrat Woldeyes, doctor and politician, born June 12, 1928; died May 14, 1999

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.